Drawing Tools for People With Hyperhydrosis

It's a widely held belief that the Ancient Masters were exactly that: masters, such as da Vinci and Vermeer, World Health Organization painted in flawlessly precise freehand. At that place are savants with steady hands, no more question. But there are else techniques to see, which David Hockney (an artist of our senesce World Health Organization also pioneered iPad art), expounds on in Secret Cognition: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Honest-to-goodness Masters, in which atomic number 2 lays out exactly how European painters used mirrors and lenses to create their compositionally perfect portraits.

That popeyed Golan Levin, an interaction designer and a tech performance creative person of sorts–and one of Fast Keep company's hoi polloi shaping the future of design in 2012. Why? "Mostly because it seemed like a truth, but none of my colleagues talked about IT," he tells CO.Aim. Levin teaches at Carnegie Mellon and also sits on the admission faculty. "Whol these students come to me from high, and they think art equals house painting, and painting equals realistic painting. They're being set up to believe they need superhuman powers."

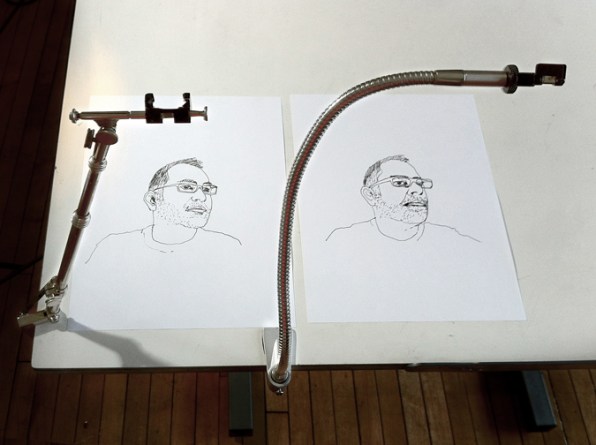

Pablo Garcia, an art professor at the School of the Art Bring in Chicago, has been hip to the (contentious) idea for some years and has amassed an extensive collecting of optics. He offered to Lashkar-e-Toiba Levin sample out a camera lucida, indefinite of the tools Hockney says the Old Masters in use to bewitch their subjects more realistically. Levin loved information technology, and the duo decided to take a leak a 21st-centred version.

A camera lucida is a simple political machine: A small prism reflects the image of the theme so the viewer can understand their own hand, plus the image, and trace a more accurate rendering onto the paper. The effect isn't far off from the Google Glass telecasting demos we've been eyesight. There are layers of images available in your line of vision–for you to utilise in roughly smart way. Merely the only lucidas nonetheless available are collectibles, and run a price tag north-central of $300–more than Levin and Garcia believed college students would pay. As it turns out, manufacturing just several lucidas costs $20,000, just each additional optical prism costs just pennies.

Which is why the NeoLucida sells for $30. Information technology's perfect for Kickstarter. Since unveiling the product on May 8, Levin and Garcia are already hearing from people WHO missed down on the prototypical 2,500 they successful available. But unlike most other runaway Kickstarter hits, this isn't–operating room wasn't–reputed to be a business. "This whole thing is a performance, or an intervention, or just nontextual matter," Levin says. Luckily, the project had enough demand and interest so that just two days after going live, Levin and Garcia confirmed that there will be an unlimited second output run, conducted away professional manufacturers.

The effects of getting the NeoLucidas out into the market should be interesting. Animators, filmmakers, and diagram-mappers are each groups that Levin and Garcia acknowledgment as rational customers. Because for whol the advancements we experience with graphic illustration and photography, people still want amass their sleeves and draw care an yellowed master.

The plan has already lifted about $400,000, far beyond its goal of $15,000. Support the campaign hither.

Drawing Tools for People With Hyperhydrosis

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/1672559/kickstarting-a-30-optical-tool-for-drawing-with-camera-like-accuracy

0 Response to "Drawing Tools for People With Hyperhydrosis"

Enregistrer un commentaire